How Fast Should Your Strength Gains Be?

Hello, World!

When you first start lifting, progress can feel electric. The weight on the bar goes up nearly every week, and you feel stronger every session. But then, inevitably, things start to slow down. That rapid climb becomes a steadier, more challenging grind. This is the point where many people get frustrated, start questioning their program, or wonder if they’ve hit their "genetic potential."

The truth is, this slowdown isn't just normal - it's a predictable and a necessary part of getting stronger. The trap many fall into is believing that the journey from a beginner to an intermediate or advanced lifter is a straight line, when in reality; it's a curve. Understanding this curve is crucial to setting realistic goals, staying motivated, and training intelligently for the long haul, as when you can appreciate and respect this, you’ll stop worrying about “trying to get back to when progression was like this ______”; and be able to enjoy your training far more.

This article will break down the science of strength adaptation and provide a clear, evidence-based framework for what you can expect at every stage of your lifting journey.

Understanding Adaptation

To know where you're going, you need to understand the engine driving you forward. Strength gain is a biological process governed by a few key principles.

The Stress-Recovery-Adaptation Cycle

At its core, all progress comes from the Stress-Recovery-Adaptation (SRA) cycle.

Stress: Your training session is the stressor. You lift weights, which causes microscopic damage to your muscle fibres and creates fatigue.

Recovery: With proper rest, nutrition, and sleep, your body repairs this damage.

Adaptation: Your body doesn't just repair to its previous state; it adapts by rebuilding the muscle fibres to be stronger and more resilient than before. This is called "supercompensation".

For a beginner, this cycle is very short - often just 24 to 48 hours. That’s why someone new to lifting can add weight to the bar almost every workout. For a more experienced lifter, the stress needed to disrupt the body is much greater, and the recovery and adaptation process takes far longer, sometimes weeks or months.

The Law of Diminishing Returns: The End of "Newbie Gains"

The body is incredibly efficient. When you introduce a new stimulus (like lifting), it adapts quickly. But as you repeat that stimulus, the body gets used to it, and the adaptive response gets smaller. This is the law of diminishing returns, and why the explosive progress you see in your first year - often called "newbie gains"- doesn't last forever.

To keep making progress, the training stimulus has to evolve through progressive overload - manipulating variables like weight, sets, reps, or exercise selection to keep challenging your body.

Neurological Vs Muscle Gains

The strength surge in the first 3-12 months of training is primarily driven by your nervous system, not just muscle growth. Your brain gets better at:

Learning the movement patterns of the lifts.

Recruiting more muscle fibres for each contraction.

Improving coordination between different muscle groups.

Your brain is essentially learning to use the muscle you already have more efficiently. This is a fast process. Building new muscle tissue (hypertrophy), on the other hand, is a much slower, more metabolically demanding process. The transition from a beginner to an intermediate lifter happens when you've exhausted most of this rapid neurological potential. From that point on, building new muscle becomes the primary driver of strength, which is why the rate of progress naturally slows down.

Where Are You on Your Strength Journey?

To set realistic goals, you first need to identify your training level. This needs a little more thought than simply how long you've been in the gym; it's about how long you’ve consistently been training with intelligent or structured programming and where your current strength is at, relative to your bodyweight. We can break it down into four main stages:

Figure 1 - Athlete Classification Matrix

The Beginner: You're in your first year of consistent, structured training. You can add weight to your main lifts on a weekly, or even session-to-session, basis. Your focus should be on mastering technique and building a solid foundation.

The Intermediate: You've been training consistently for 1-4 years. Linear progress has stopped, and you now need a more structured program (periodisation) to make gains. Progress is measured month-to-month, not week-to-week. This is where the real grind begins, and patience becomes your greatest asset.

The Advanced Lifter: After 5+ years of dedicated training, you are approaching your genetic potential. Progress is slow and hard-won, measured over entire 12-20 week training cycles. Gains are marginal, but every small victory is a testament to meticulous planning and dedication.

The Elite Lifter: You are among the top competitors in the sport. Progress is rare and may only be seen on an annual basis, requiring highly specialised programming and an unwavering commitment to all aspects of training and recovery.

Note: there is some crossover between categories such as where a lifter has worked up to an intermediate stage, taken time off due to “life”, injury etc. that may find themselves more towards/in the beginner category upon resuming training - you’re not “doomed” to your category should you need to take time off!

How Fast Should You Actually Be Getting Stronger?

Now for some numbers. The following tables provide a realistic look at what you can expect for monthly gains in your one-rep max (1RM) for the big powerlifting and Olympic lifts. The ranges account for individual differences, which we'll cover in the next section.

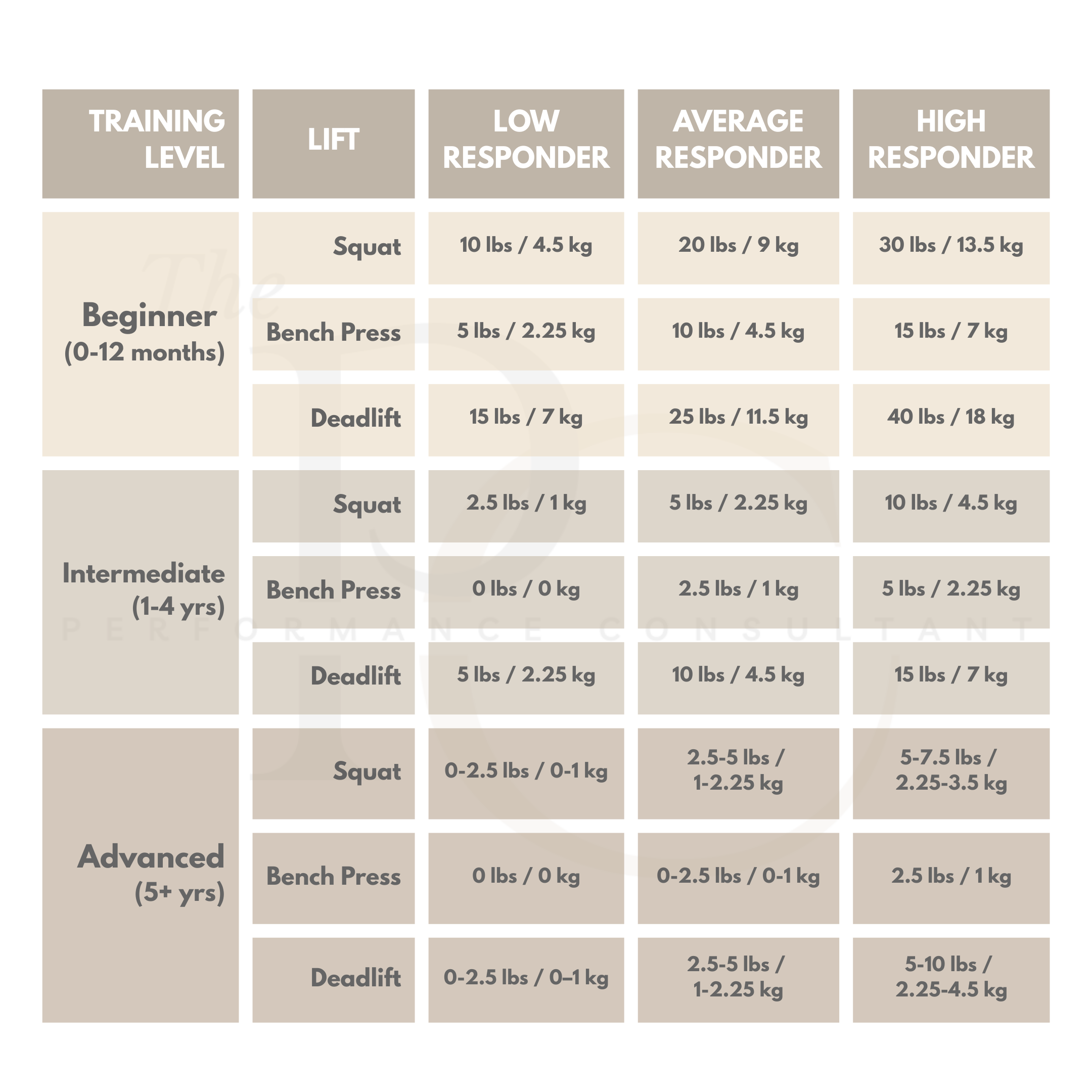

Powerlifting: Squat, Bench Press & Deadlift

These lifts are the foundation of static strength. Progress is fairly predictable as you move through the stages.

Table 2: Estimated Monthly 1RM Gains in Powerlifting (lbs / kg)

Olympic Weightlifting: Snatch & Clean & Jerk

The Olympic lifts are a blend of strength and skill. For beginners, progress is almost entirely about technique. It's not uncommon for a new lifter's max to jump dramatically when a technical element "clicks." Once technique is established, progress becomes more tied to underlying strength in the squat and pulls.

Table 3: Estimated Monthly 1RM Gains in Olympic Weightlifting (lbs / kg & %)

Note: Beginner gains are highly variable and depend on technical acquisition. The listed values represent potential progress under consistent, quality coaching, without the use of performance enhancing drugs.

The X-Factors: What Speeds Up or Slows Down Your Progress?

The tables above show a range for "Low," "Average," and "High" responders. Where you fall on that spectrum depends on several key factors:

Genetic Blueprint: Genetics play a significant role, influencing everything from your skeletal structure and muscle fibre type to your natural hormone levels. While genetics set your ultimate ceiling, it's crucial to remember that everyone can get dramatically stronger than their untrained selves. Smart training and recovery will always trump "bad" genetics which should be carefully moderated so as not to be viewed as a “death sentence”.

Training & Program Design: This is the most powerful variable you can control which fortunately, I take care of for you. A program built on the principles of specificity (training for your goal) and progressive overload (consistently increasing the challenge) is non-negotiable. A beginner can thrive on a simple linear program, while an intermediate or advanced lifter needs a more complex, periodised plan to manage fatigue and continue driving progress.

Life Outside the Gym: You don't get stronger in the gym; you get stronger when you recover from the work you did in the gym.

Nutrition: Food provides the fuel for performance and the raw materials for repair. Adequate protein (1.6 to 2.2 grams per kilogram of bodyweight) is essential for muscle protein synthesis, while carbohydrates are critical for fuelling high-intensity workouts and replenishing energy stores.

Sleep: This is the most critical recovery tool. During deep sleep, your body releases anabolic hormones like growth hormone and repairs damaged tissue. Consistently poor sleep will suppress these processes, elevate stress hormones, and severely handicap your progress. 8 hours should be a non-negotiable if you’re wanting to maximise strength or muscle growth, with an absolute minimum being 7 hours. Secondary to that should be that one hour before bed time, work gets put away and you get off your phone (especially social media!).

Stress: It would be foolish to aspire towards becoming “immune” to stress; it’s a natural part of life and will happen - and often at very inconvenient times! However, we can control how we respond to stress. I have written entire modules for courses on stress alone, but one of the most simple and impactful things you can do is to minimise the predictable stressors in your life. Set off 10 minutes early. Pack a spare serving of protein powder. Make sure your meal prep is done ahead of the week, etc. Control what you can control, and the uncontrollable won’t control you.

The Marathon of Strength

Developing maximal strength is a long-term journey - a marathon, not a sprint. The explosive progress of your first year is an exciting but temporary phase that must be viewed as such. True, lasting strength is built through years of consistent effort, intelligent programming, and a disciplined approach to recovery.

Celebrate the rapid wins of your beginner phase. Embrace the grind of the intermediate years. Respect the meticulous effort required for advanced progress. And remember, if success was given so easily, everyone would have it, and the achievements wouldn’t be half as attractive. By understanding the process, you can avoid frustration, stay motivated, and enjoy the lifelong pursuit of becoming a stronger version of yourself. Hopefully this guide has helped you set some realistic expectations for yourself.

Love,

Coach